Ann English charged with murder after death of daughter.

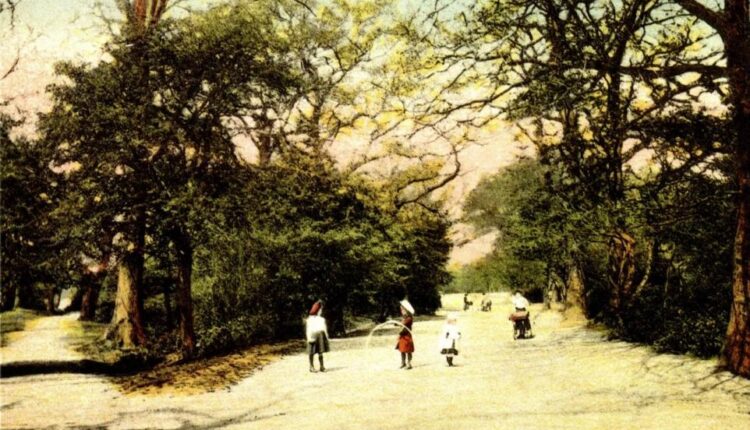

The sun had long set below the horizon, and a chill settled over Southampton Common.

Shortly after dark, Joseph Wren, a labourer working on the new Southampton-Dorchester railway, took a shortcut across the open land.

As he leapt over a dry ditch, his foot caught on something yielding, and he looked down, his heart racing in his throat.

A young girl’s small, lifeless body was partially obscured by a scattering of dry leaves.

The scene had an unsettling freshness to it, as if the child had only been there for a short time. Shaken, Wren scrambled back onto the path and ran, his hurried footsteps echoing on the peaceful road.

He flagged down a passing woman, Ann Biggs, and they waited for PC Leigh.

Bishopstoke The officer, lantern held aloft, carefully examined the situation. He noticed that the body appeared to have been moved, dragged further along the ditch than it had originally been.

In that first location, the earth was clearly disturbed, leaving a distinct impression of a small left arm and a face pressed into the dirt. The child’s body was transported to the police station for a postmortem examination.

Local surgeon Patrick Mackey concluded that the girl died from a “diseased stomach.” However, he made an important observation.

“Immediately after its death,” Mackey stated, “it was placed in that situation and pressed down with some violence, which explains the marks on the body.” The stomach disease had been present for quite some time.

He then delivered the damning final line of his statement: “If pressure was applied to a child with a diseased stomach, it would result in death.”

With no other leads, the inquest jury returned the verdict ‘Found dead.’ The police were faced with the difficult and pressing task of identifying the mother.

Their only hope was that someone would recognise the unique nightgown in which the infant was wrapped. Interestingly, their request for information was answered. A fellow Poor House resident came forward to identify the nightgown.

Within hours, Police Chief Inspector Enright identified the mother as Ann English, a 27-year-old woman from Bramshaw on the outskirts of the New Forest who had been working in town.

Then a dramatic development occurred.

Ann English was arrested 10 days after the child was discovered, on June 6, 1847.

The body was discovered while the Southampton-Dorchester railway line was under construction. On that day, she wore a “dark blue figured stuff gown, a white Paisley shawl, a fancy dressed bonnet with artificial flowers,” and her demeanour was unreadable.

Patrick Mackey’s final, significant statement about the pressure on the child’s stomach convinced police that the child, now named Matilda, died in an unnatural manner.

Ann English, described as “a comely looking woman,” was officially charged with murder.

The following morning, she appeared before the magistrates. Inspector Enright laid out the evidence against her, revealing that she had left her home with the child, who appeared “fit and well.”

When she returned, she was alone, claiming her daughter had been detained in a hospital and refusing to name her father.

After Enright requested a remand in custody, English requested to make a statement, which was granted.

She told the court a heartbreaking story about their journey from Bishopstoke to Southampton, including spending two nights on the street in the “wet and cold,” and eating bread, cheese, rum, and water in a pub with her daughter.

English claimed the child became ill after they left Bishopstoke, and with their money depleted, they wandered around Southampton before heading to the Common.

“I did not like to say anything to anybody about it, so kept walking on the Common thinking it would get better,” the lady told the judge. “I sat under a tree, and the child’s condition worsened.

It had a fit and threw up some of the beer, bread, and cheese.

It had a strong fit for 30 minutes before dying.” English then described the gruesome procedure for disposing of the body.

“I then assumed I’d be accused of something and threw it into a ditch near The Cowherds Inn.

. Bramshaw. I never used violence against it, but because my mother was attached to the child, I didn’t tell her about its death.

I decided to go home and say nothing about it. I blamed her death on the strong food (she had previously been used to delicate food) and the exposure to the elements all night.

The police’ suspicions were confirmed three days later at a second remand hearing.

Ann Biggs, the woman Wren had flagged down, claimed she saw English drag her child by the foot down the ditch and lay her on her back.

Biggs revealed that English had threatened her, saying, “I was a silly girl if I ever said anything about it as I should get into trouble and herself too.”

Read more on Straightwinfortoday.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.