The UK car industry is at a crunch point – can it be saved?

A gleaming white Vivaro van slowly drove off the production line at Vauxhall’s factory in Luton, beeping its horn as workers cheered and crowded around to take photographs.

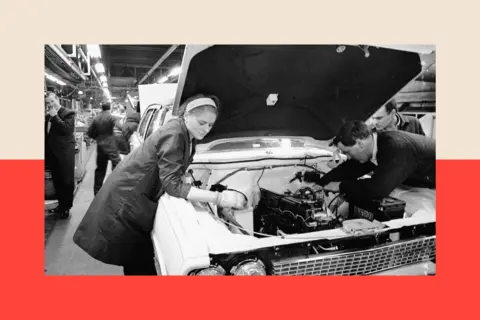

Behind it, the production line came to a halt—forever. The Luton plant began producing automobiles in 1905.

It continued to operate for the next 120 years, pausing to build tanks and aircraft engines during World War II. But on March 28, that came to an end. The factory closed due to cost-cutting measures at Vauxhall’s parent company, Stellantis.

Justin Nicholls, a production shift manager, was one of the 1,100 employees at the plant, having worked there for 38 years. “It was devastating, because it came out of the blue”, he says. “It was a complete surprise.”

It followed the closures of Honda’s car factory in Swindon in 2021 and Ford’s engine plant in Bridgend the previous year.

Together, they have come to represent an apparent long-term decline in the UK automotive sector.

Mike Hawes, the SMMT’s CEO, described the situation as “depressing”. According to the SMMT, the sector contributes about £22 billion to the economy each year, and as of 2023, automotive manufacturing employed approximately 198,000 people in the UK.

Andy Palmer, the former CEO of Aston Martin, believes the ecosystem – and the money it generates for the economy – can only survive if the industry maintains its current size.

“There is a critical mass of employment,” he adds. “Once you get below that, you see everything fall apart.

“You don’t have the university courses, you don’t have people coming across from the aero industry, you don’t have the pipeline of skilled engineers that allow the luxury firms to exist, and so on.” This could have an impact on regions that are already facing challenges.

“If we think about parts of the UK that have automotive plants, they’re often disadvantaged regions,” says David Bailey, professor of business economics at Birmingham Business School.

“Losing these good quality jobs would have a big impact in terms of wages for workers and also a knock-on effect in terms of the multiplier on the local economy.”

He is concerned with what has already been lost. “I would argue that we have already let too much of this go.

I believe once it’s gone, it’s truly gone.” The question is: can the industry recover, or is it too late?

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.