Why Dundee minister becoming chaplain to the Tartan Army was like a ‘gift from God’.

Erik Cramb watched the last whistle of Scotland’s World Cup-winning victory against Denmark last week with the bewilderment of a man who has experienced a lifetime of football highs, lows, and false dawns.

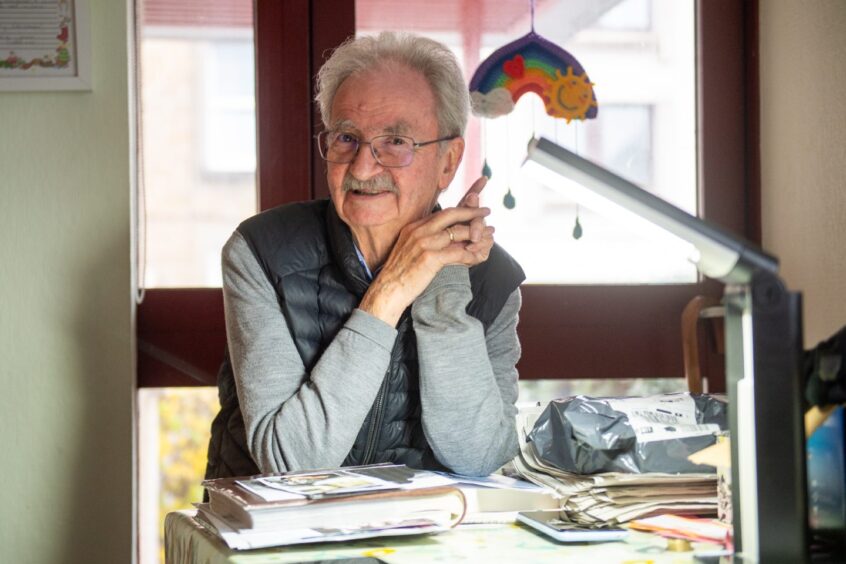

“In 80 years of watching football, I’ve never seen anything like it,” laughs the 85-year-old Dundee clergyman and social-justice advocate.

“It was so beautiful that I was almost afraid to get out of bed on Wednesday morning, in case it was all a dream. “Oh, I of little faith!”

Erik has always seen football as more than just fun.

It has served as a thread connecting his upbringing in Maryhill to his years of ministry in Glasgow, Jamaica, and Dundee, as well as the most unlikely corners of international diplomacy.

Erik, a juvenile polio survivor who became a strong table tennis player despite his withered hand and limp, says his only regret is that his infirmity stopped him from playing for his beloved Partick Thistle.

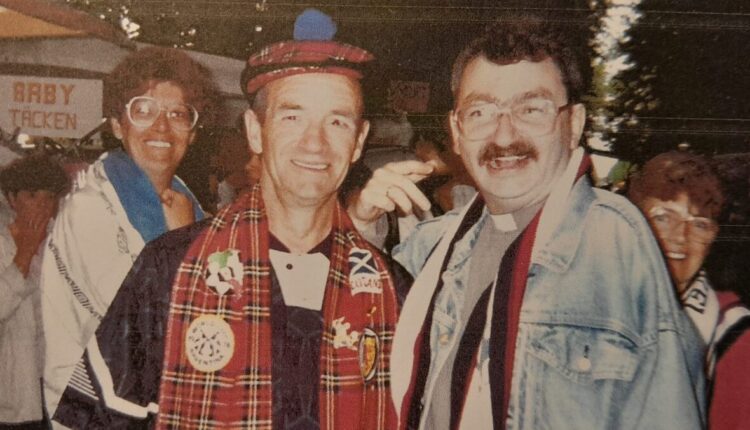

However, witnessing Scotland defeat Denmark on November 18 transported him back to 1992, when he was unexpectedly chosen official chaplain to the Tartan Army at the European Championship in Sweden.

“If you believe in God’s gifts, that was it for me,” he continues, still sounding little amazed.

‘Old ladies were helped across streets they didn’t want to cross’

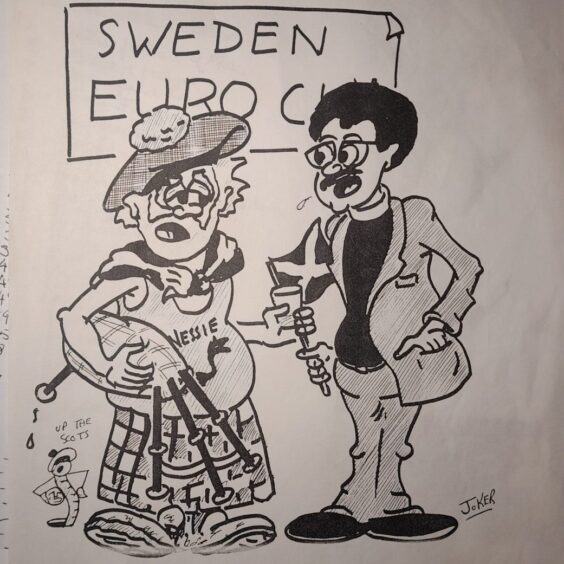

Erik’s memories of that summer are impish, vivid, and presented with the comedic timing of a man who has spent decades blending theology, comedy, and political instinct.

The Swedish football authorities, concerned about the attitude of English and German fans, had requested that each participating nation send clergy along with their supporters.

The notion was that a few dog collars may alleviate tensions at a time when hooliganism was still common.

Stockholm served as the basis for both England and Germany. Scotland was in Gothenburg. When the Tartan Army arrived, something unusual and delightful happened.

“The more trouble the English got into, the more outrageously good we were,” Erik says with humour.

“Old ladies were assisted across streets they did not wish to cross! “We were impeccable.” He laughs at the notion of thinking he had seen Paul McStay score against the CIS.

He only discovered later, via Swedish-subtitled Archie Macpherson commentary, that McStay’s strike had hit the post before cannoning off the diving goalkeeper’s head and into the net.

Then there were the chants that were cleared up following a courteous request from the organisers, and the supporters who thought they were playing the Co-operative Insurance Society because Russia, a freshly post-Soviet country, was participating as the CIS.

And don’t forget the Scots, who created songs about Sweden’s Tomas Brolin in a marquee the night England was eliminated.

“The night England went out – 24 hours before we did – people were giving me credit for divine intervention,” he says with a smile. “I’ll take it.” Denmark, of course, won the tournament.”

A new home in Dundee

Erik recounts The Courier these anecdotes with passion and wit while visiting his Broughty Ferry sheltered housing community. His route to the Tartan Army began long before 1992, and even before Dundee.

However, Dundee is where Erik’s life, career, and identity are most deeply established. The father of five arrived in 1989, hoping to stay for five years.

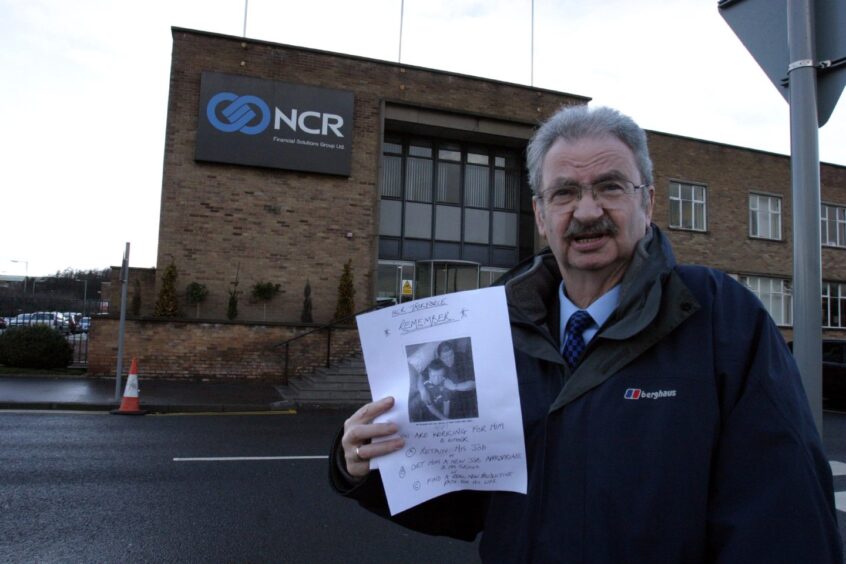

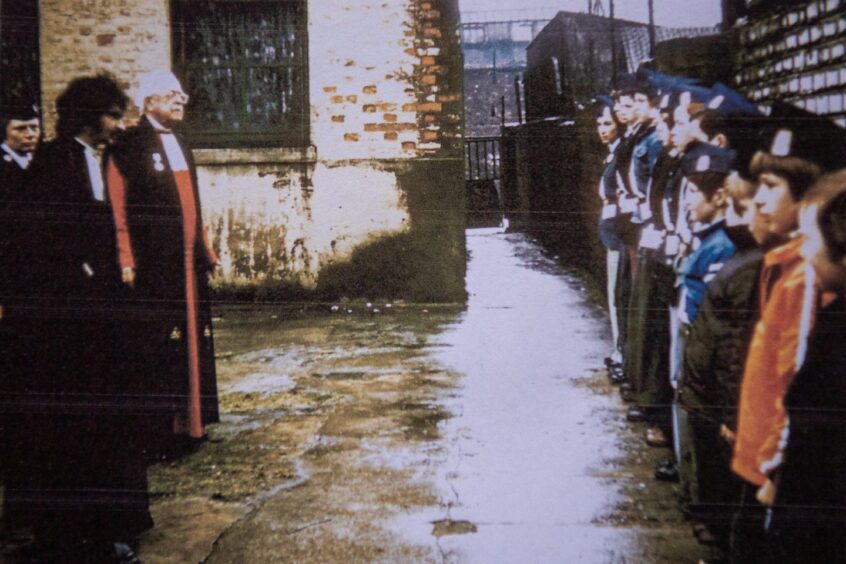

The Church of Scotland pastor had been appointed industrial chaplain, a position that took him to factory canteens, picket lines, and union halls just as Dundee was experiencing some of its most volatile economic times.

However, after a few months, he understood he had discovered a city unlike any other he had served in.

“In this wee city,” he continues, “if you’re interested in work, politics, and economics, you can dip your finger into whatever pie you want.”

Dundee allows you to get involved. “I thought I’d be back in Glasgow within five years – but fate, and family, had other ideas.”

Does Erik favour a Dundee football team?

The huge manse on Clepington Road immediately became a hub of parish activity, union meetings, and late-night theological debates.

And it was over the garden wall that football helped him integrate into Dundee’s culture. “Next door was Dr Leadbetter – Dundee United’s club doctor,” mutters Erik. “My kid Donald had a United jersey.

I recall him leaping up and down in the back garden to peek over the wall as Dr. Leadbetter was cutting the grass. That was his opportunity: ‘That’s the United doctor!'”

Erik says he remained neutral as a minister. But he says he has a soft spot for Dundee FC’s underdog status. “I’ve got a wee lean towards Dundee,” he says, smiling.

“But I’d like to see them both doing well.” Football also offered an unexpected glimpse into the city’s public life.

Dundee’s municipal leaders were frequently seen on its terraces. One memory still makes him laugh:

a prominent Tayside politician – “a good friend” – erupting into a triumphant, completely unrestrained “YAAAAAS!” after Dundee United defeated Partick Thistle in the 1995-96 play-off.

“I knew I’d left my working-class roots behind when I found myself eating a pie off a china plate at Tannadice!” he grins.

Strikes, solidarity and a city full of stories

If football provided opportunities, the industrial battles of the late 1980s and 1990s cemented Erik’s place in the civic fabric.

The Albacom strike marked his first significant test in the city. It was a protracted, bruising conflict in which he showed up at the picket line every day, merely for ‘a cup of coffee and a chat’.

“It was not heroic; it was what was required. People needed guidance, someone to listen, and someone who was not in management or politically connected.

“Just someone there.” Then followed the Timex debate in 1993, which was violent, famous, and nationally relevant.

“They were the same old repeats,” he explains. “But Dundee is a town where you stand by others. That was always the core of everything.”

His job put him in constant touch with Dundee District Council, Tayside Regional Council, and, following local government reorganisation in 1996, the newly constituted Dundee City Council.

He became both an ally and an irritant: the conscience who posed things others didn’t want to hear.

Glasgow roots and the making of a minister

To understand Erik’s motivations during his Dundee years, look back to his youth in Glasgow. He was born during the war and suffered polio at the age of nine months.

The disease could have been a defining factor: frequent hospital stays, metal callipers, and what he refers to as his “Dracula walk”. But he didn’t let it define him. His parents urged that he attend mainstream schools.

Every Friday night, his primary teacher, Mrs McCrorie, would collect and give his homework. Erik’s mother died when he was eleven. His father, a sheet-metal worker at Yarrows, worked long shifts.

Money was tight. Church became significant almost by accident.

“It started as a way to chat up women,” he says. “But a deaconess spoke about Jesus and the outsider, and the idea of standing with the people nobody else wanted got under my skin.”

At Iona, he met George MacLeod, the founder of the Iona Community, a towering figure whose combination of poetry, justice, and faith forever moulded Erik’s theology.

He realised he was good at preaching. “Good enough that it can become an ego trip,” he points out.

And he discovered a rage against injustice that subsequently grew in Dundee.

Ministry took him far from Glasgow Gallowgate to violent, politically unstable Jamaica, then to Yoker, where his anti-nuclear convictions clashed with ministering to a parish whose families relied on Yarrow Shipbuilders, and eventually Dundee.

“That tension – of loving people whose work you opposed – taught me everything,” he says.

Love, loss and the book he finally wrote

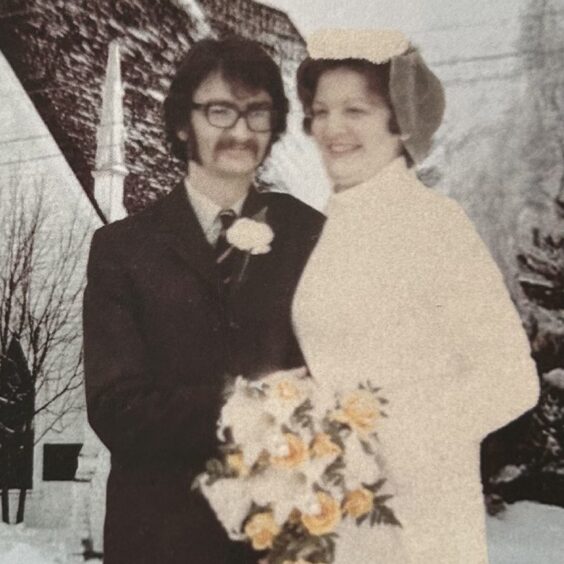

Alongside him through all of it was his wife Elizabeth, whom he met in Canada. They were married for 50 years. Her death from cancer four years ago reshaped his theology, his understanding of heaven, and the book he had spent years avoiding writing.

“She said to me the idea of a life to come, safe in the arms of Jesus where she’d wait for me, didn’t make sense,” he says quietly.

“And I agreed. We realised we’d already had our heaven. We’d had 50 years and a few months of it.”

For two years after her death, he couldn’t bring himself to write the memoir she had insisted he finish. Eventually he did.

The Bride Wore Wellies is part memoir, part theological reflection, part love story – covering his life in Glasgow, his family’s time in Jamaica, his decades in Dundee, and the faith that shaped all three.

The title refers to Elizabeth trudging through snow in wellies on the way to their wedding.

A faith that still asks questions

Erik insists he has not “lost” his faith. But he has reshaped it.

He now sees the Bible as a “treasure chest of wisdom”, not a rulebook. He views judgment as a continuous discernment, not a final courtroom.

And he believes modern science – the vastness of the universe described by Sir David Attenborough and Professor Brian Cox – demands new interpretations.

He is glad that a top Oxford-Cambridge scholar of the Gospel of Mark has supported his theological views.

However, he admits that the wider church does not always agree with him, saying, “Someone once described me as ‘an irritating pimple on the bum of the church’ – which I took as a compliment.”

Erik has been retired from the church for over 20 years and refuses to be defined by his disability. “I spent most of my working life being as able as I could,” he maintains.

However, via his volunteer work with the Dundee Pensioners’ Forum, he is still very concerned about welfare cuts, universal credit, and the erosion of support for vulnerable people.

Read more on Straightwinfortoday.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.